The Changing Landscape of Russia's Emigration from 1990 to 2020: Trends and Determinants

скачать Авторы:

- Aleshkovski, Ivan A. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Gasparishvili, Alexander - подписаться на статьи автора

- Grebenyuk, Aleksandr - подписаться на статьи автора

Журнал: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 14, Number 1 / May 2023 - подписаться на статьи журнала

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2023.01.04

Ivan Aleshkovski, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

Alexander Gasparishvili, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia; RUDN University, Moscow, Russia

Aleksandr Grebenyuk, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

The profound socio-economic and political transformations that have occurred in post-Soviet Russia had a significant impact on Russian emigration. Emigration is becoming increasingly threatening for Russia since it can lead to the loss of its demographic, socio-economic and intellectual potential. According to our estimates, the actual Russian emigration over the past 30 years significantly exceeds the official statistical figures. The present study identifies three main periods in the evolution of Russian emigration from 1990 to 2020 as well as different determinants of emigration, socio-economic characteristics of emigrants, and the emigration channels and routes. The study of the transformation of ‘push’ factors, the list of which tends to shift in the direction of narrowing the spectrum and increasing the influence of economically deterministic reasons for emigration, plays an important role in the research. The transition from one period to another was caused by socioeconomic and political changes in Russia, as well as by some changes in the migration legislation. At the third stage, which ended in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the list of reasons for emigration narrowed significantly. Russian emigration in the specified became more diverse in terms of emigration channels and destination countries. To a certain extent, new Russian emigrants considered themselves as global citizens who were well aware of peculiarities of living and working abroad; they speak one or more foreign languages and have fewer difficulties in adapting to a new country. The study is based on the data from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat), foreign statistical agencies, the OECD and the UN DESA Population Division.

Keywords: Russian emigration, emigration attitudes, international migration, migration channels, migration factors.

Introduction

The word ‘emigration’ comes from the Latin word ‘emigro’, meaning ‘to leave a place’. Emigration is the act of moving from one's country of nationality or habitual residence to another country, so that the country of destination effectively becomes one's new country of habitual residence. The definition of who is an emigrant may vary from one country to another (IOM 2019: 63–64).

Depending on the motives for moving, emigration can be either voluntary or forced. Voluntary emigration means that the country a migrant is leaving has inferior conditions or prospects of life compared to those in the countries to which he or she is moving. Forced migrants are people who are forced to leave their place of residence because of current circumstances, such as violence committed against them or the possibility of being subjected to such violence, as well as due to the existing danger (military, religious or political), natural or man-made emergencies.

The term ‘Russian emigrants’ includes people who went abroad from Russia to take up permanent residence in different historical periods. At the same time, after naturalization (acquisition of citizenship of the host country) some countries stop considering foreigners as immigrants. As a result, they are no longer counted in foreign statistics as immigrants, but are included into the indicator ‘foreign-born’ (‘born in Russia’). In turn, naturalization abroad may be accompanied by the retention of Russian citizenship (Ryazantsev 2018).

Changes in the political, economic and social spheres of life in Russia that occurred following the collapse of the Soviet Union have led to a radical transformation of migration processes in the post-Soviet space and exacerbated the problem of emigration of Russian citizens. Over the period of 30 years (from 1990 to 2020), millions of Russians were left their homeland. The largest migration flows were to developed countries: the USA, Germany, Israel, Canada, Spain, Italy and France. Migration flows varied both in terms of size and category of migrants, as well as in terms of the main reasons for emigration.

The conducted studies of emigration from contemporary Russia, as well as data from Russian and foreign sociological research, indicate that the factors determining Russian emigration, the structure, channels, intensity and direction of emigration have changed in the post-Soviet period.

The objective of this study was to develop a periodization of Russian emigration in the post-Soviet period according to the factors determining the resettlement.

Methods and Data Sources

According to the push-pull theory of migration, there are four groups of factors that set the direction and intensity of migration flows. The first group represents the ‘push’ factors associated with the country of emigration, and it creates emigration attitudes. The second group represents the ‘pull’ factors associated with the country of potential emigration and includes positive factors that shape a person's attitude toward moving to that country. The other two groups of factors represent ‘confounding’ circumstances and factors related to subjective characteristics of migrants (Lee 1966: 47–57). This study, however, focuses on the first two groups.

Our research is also based on the human capital theory as applied to population migration. Within this theory, one can identify three main factors influencing the decision to emigrate, that is, the employment conditions in the home country and in the potential country of destination, age, and the moving costs (Schultz 1981: 23). In the context of emigration from Russia, one has to make sure the employment conditions abroad will cover the possible moving costs, so that Russians strive for the maximum capitalization of their human capital.

Analyzing the reasons for migration published by Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat), one can see that the so-called personal and family reasons as well as ‘other reasons’ traditionally dominate among them (Rosstat 2000–2021). At the same time, these reasons are very vague and often include a number of other reasons, and do not provide complete information about the reasons for emigration. The factors influencing the decision to emigrate can be identified by indirect methods in the course of sociological surveys of the population's migration intentions or migration attitudes. One should note that the emigration attitude only implies the individual's desire or plans to emigrate, but not their actual implementation.

As part of the study, we identified a number of so-called ‘instrumental’ reasons that influence the statistics on Russian emigration. These include the desire to be able to move freely between countries and conduct business or work abroad. For these purposes, the practice of obtaining a second citizenship (or residence permit) abroad without renouncing Russian citizenship is widespread.

The theoretical base of the study is formed by the works of Russian and foreign scientists on the issues of emigration from Russia (Akhiezer 1999; Aleshkovski et al. 2018; Aleshkovski et al. 2020; Baykov et al. 2018; Chudinovskikh and Stepanova 2020; Denisenko 2003, 2013, 2020; Denisenko et al. 2003; Herbst and Erofeev 2019; Iontsev et al. 2001; Iontsev et al. 2016; Mukomel 2005; Polyan 2005; Potapova 2017; Ryazantsev 2016, 2018; Riazantsev et al. 2018; Ryazantsev and Grebenyuk 2014; Ryazantsev and Khramova, 2018; Savoskul 2016; Vishnevsky and Zayonchkovskaya 1991; Vorobyeva, Grebenyuk 2016; Ushkalov and Malakha 1999; Zayonchkovskaya 2003). The empirical base of the study is data from the Rosstat and those of the main countries of destination of Russian emigrants, the OECD and the UN DESA Population Division, as well as data from Russian and foreign sociological research (WCIOM, LEVADA, ROMIR, Atlantic Council).

Results

Our analysis of emigration flows from Russia using the theory of ‘push-pull factors’ and theory of human capital allowed us to single out three periods in the evolution of Russian emigration from 1990 to 2020 (see Table 1). Every period was characterized by push factors, the emigration potential of population, qualitative changes in the intensity and structure of emigration flows, and the directions of emigration. The transition from one period to another was due to socio-economic and political changes in the country, as well as changes in Russian and foreign migration legislation.

Table 1

Periodization of Russian emigration in 1990–2020

|

Period |

Time interval |

Emigration scale estimates, |

|

First |

1990–1999 |

3.03–4.1 |

|

Second |

2000–2011 |

0.83–1.5 |

|

Third |

2012–2020 |

0.53–0.75 |

First period (1990–1999)

The transformation of the socio-economic and political conditions of life in the USSR led to dramatic changes in international migration in Russia at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. The deterioration of the general socio-economic situation in Russia, a decline in living standards combined with political instability and inter-ethnic conflicts, on the one hand, and the fall of the Iron Curtain, on the other, unleashed a powerful wave of emigration (Akhiezer 1999; Vishnevsky and Zayonchkovskaya 1991). The scale of emigration began to grow in the late 1980s. Thus, in 1990, 103.7 thousand people left Russia, although the USSR remained formally a closed country. It was not until late May 1991, that the USSR adopted a law permitting its citizens to travel abroad freely (Law of the USSR of 1991). The right to travel abroad and return home was enshrined in the Russian Constitution of 1993. In just a few years, Russia has gone from being a closed country to an active participant in international migration processes, acting simultaneously as a country of origin, a country of destination and a country of transit for migrants).

According to official Russian statistics, about 3 mln people emigrated from Russia in the 1990s (see Table 2). However, the Rosstat counts as ‘emigrants’ only those Russian citizens who, upon their leaving Russia, cancelled their permanent residence permit at their permanent place of residence in Russia. At the same time, this procedure is obligatory, and many Russian citizens, while living permanently abroad, keep their residence permit in Russia. Therefore, some of the emigrants are included in the official Russian statistics. According to the research conducted, foreign sources more accurately reflect the scale of Russian emigration (Aleshkovski et al. 2018; Chudinovskikh and Stepanova 2020; Denisenko 2003, 2013; Ryazantsev 2018; Ryazantsev et al. 2021; Vorobyeva, Grebenyuk 2016).

Table 2

Dynamics of Russian emigration in the 1990s

|

Year |

The number of emigrants, |

% compared |

|

1990 |

103.7 |

218 |

|

1991 |

88.3 |

85 |

|

1992 |

704.1 |

797 |

|

1993 |

493.1 |

70 |

|

1994 |

345.6 |

70 |

|

1995 |

347.3 |

100 |

|

1996 |

291.6 |

84 |

|

1997 |

233.0 |

80 |

|

1998 |

213.4 |

92 |

|

1999 |

215.0 |

101 |

Note: The number of persons who received permission to move to another country for permanent residence in 1990–1991.

Source: Data were collected from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service Database (EMISS 2021).

Our comparison of Rosstat data with the OECD and UN data on the number of Russian immigrants in the main destination countries reveals an underestimation of the intensity of emigration from Russia. Thus, according to Rosstat data, emigration from Russia to Germany amounted to 570,832 people in the 1990s, while according to the UN, the number of Russian immigrants in Germany in the 1990s increased by 826,459 people (UN 2019; Rosstat 2000: 320). According to our estimates, the total number of emigrants from Russia in the 1990s exceeded 4.1 million people (Aleshkovski et al. 2018; Vorobyeva and Grebenuk 2016).

The dynamics of the number of emigrants is closely related to changes in the socio-economic and political situation in Russia. Surges in emigration can be caused by the influence of a number of factors, including temporal and situational ones. A number of socio-political events in the 1990s (the Ossetian-Ingush and Chechen armed conflicts, the political crisis of 1993) became catalysts for emigration, involving a wide range of social groups (Iontsev et al. 2001).

In 1992, the number of Russian emigrants reached an all-time high of more than 700,000 people. That year, the decline in real GDP reached 15 per cent, the level of consumer prices increased 26-fold and more than 3.5 million people became unemployed (Rosstat 1996: 93, 285, 376). In the early 1990s, some Russian and foreign experts made apocalyptic prediction that millions of people would leave Russia in the coming years and that the country would lose most of its intellectual elite. The survey conducted in 1991 by the Center for Human Demography and Ecology showed that 2 to 5 mln citizens would leave the country in the next five years. Proceeding from the results of a survey conducted by the University of Toronto in 1991, the emigration potential can be estimated at 4.75–8.9 million people. The maximum estimates made by some experts were 30–40 million of potential emigrants (Aron 1991; Vishnevsky and Zayonchkovskaya 1991; Brym 1992: 390).

In addition to quantitative losses of the population, Russia suffered significant losses of human capital. It is estimated that in 1991–1994 alone, the country lost 150,000 people working in the field of science, education, and the medical industry. By 1994, more than 30,000 Russian scientists were working in the United States and Israel, 4,000, in Germany, and more than 600 in France (Ushkalov and Malakha 1999).

With the stabilization of the internal political and socio-economic situation in Russia and tightening of the immigration policy in Western countries, the scale of Russian emigration has been steadily decreasing. The 1998 Russian financial crisis led to a short-term increase in the number of emigrants from Russia, but the rate of emigration began to slow in April 1999, signaling the normalization of the economic situation in the country.

Considering the geographical structure of emigration, one should note that in the 1990s, the main countries of destination for immigrants from Russia (excluding the post-Soviet countries) were Germany, Israel and the United States. Thus, these three countries received 94.9 per cent of Russian emigrants in 1992, 95.6 per cent in 1995, and 92.6 per cent in 1999 (see Table 3).

In the first half of the 1990s, due to the scarcity of citizens' financial savings, the opportunities for resettlement abroad depended largely on the immigration policies of the host countries. Ethnic migrants and representatives of the country's intellectual elite (scientists and highly qualified specialists) had the best chances of receiving support in the host countries (Akhiezer 1999: 171–172). In the first half of the 1990s, the main channels of emigration from Russia were ethnic emigration (a significant proportion of those leaving were families of ethnic Germans, Jews, Greeks, Meskhetian Turks, while Russians tended to leave as part of mixed families) and ‘brain drain’ (intellectual emigration). In the 1993–1995 period, about 62 per cent of all Russian emigrants were ethnic Jews and Germans (99.8 per cent of Germans went to Germany, and about 50 per cent of Jews went to Israel and about 35 per cent to the United States). One in five Russian emigrants had a higher or incomplete higher education, including 32.5 per cent of those who went to Israel, 48 per cent to the USA, and 59 per cent to Canada (compared with 13.3 per cent of the Russian population as a whole) (Ushkalov and Malakha 1999: 68). Despite the ethnic nature of migration, economic factors were the main determinants of migration for many emigrants, with nationality becoming a channel to facilitate movement abroad (Savoskul 2016).

Table 3

The share of the main destination countries in the emigration flow from Russia

|

Year |

Germany |

Israel |

USA |

Total |

|

1990 |

32.6 % |

58.8 % |

2.2 % |

93.6 % |

|

1991 |

38.2 % |

43.9 % |

12.5 % |

94.5 % |

|

1992 |

60.8 % |

21.3 % |

12.8 % |

94.9 % |

|

1993 |

64.1 % |

17.9 % |

13.1 % |

95.1 % |

|

1994 |

66.0 % |

16.1 % |

13.1 % |

95.1 % |

|

1995 |

72.1 % |

13.8 % |

9.7 % |

95.6 % |

|

1996 |

66.6 % |

14.8 % |

12.7 % |

94.2 % |

|

1997 |

61.5 % |

17.0 % |

14.7 % |

93.2 % |

|

1998 |

58.8 % |

20.2 % |

12.9 % |

91.8 % |

|

1999 |

48.8 % |

33.5 % |

10.2 % |

92.6 % |

Note: Except for emigrants to the post-Soviet states.

Source: Calculated from the data of the Demographic Yearbook. Мoscow: Goskomstat, 2001. P. 336.

In the second half of the 1990s, as members of the above-mentioned ethnic groups left the country, and host countries tightened the rules for accepting immigrants from post-Soviet countries, the importance of the ethnic component diminished, and the proportion of Russians leaving on their own or as part of mixed marriages increased in emigration flows (from 18.7 per cent in 1993 to 40.4 per cent in 1999) (Lokosov and Ry-bakovskiy 2014: 69).

During those years, new channels of emigration developed: 1) labour migration (Russian migrants filled various niches in the labor markets of foreign countries); 2) forced migration (the exodus from the Chechen conflict zone was one of the few grounds for granting refugee status to immigrants from Russia); 3) educational migration, which in a significant number of cases became an intermediate stage to further emigration; 4) marriage migration of women (‘bride migration’) who left Russia in search of a foreign husband or went to their spouses' country of permanent residence; 5) children's migration through international adoption (Aleshkovski et al. 2018; Denisenko 2003; Vorobyeva and Grebenuk 2016; Ushkalov and Malakha 1999; Zajonchkovskaya 2003). The primary accumulation of capital in Russia was still ongoing, so there was no large-scale business migration with the aim of investing or starting a business abroad.

In the second half of the 1990s, residents not only of Moscow and St. Petersburg, but also of other Russian regions became increasingly involved in emigration. In 1992, Moscow and St. Petersburg accounted for 40 per cent of all emigrants, while in 1999, it was only 11 per cent. The main exodus regions were the Altai and Krasnodar territories, Volgograd, Kemerovo, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Orenburg, Rostov, Saratov, Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk regions, and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (Ushkalov and Malakha 1999: 68; Rosstat 2000: 330).

The geography of destination countries was expanding. Communities of migrants who left Russia in the 1990s were formed in Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, the Republic of Korea, Turkey, Czech Republic, Finland, Switzerland, Japan, and Cyprus. According to the UN, in 2000 immigrants from Russia lived in 98 countries of the world (UN 1999).

The analysis of the results of sociological research and of publications in the 1990s, allows making a conclusion that the key factors of emigration in the 1990s were powerful socioeconomic and political push factors (collectively characterized by respondents as ‘the current state of society’). At the same time, the emigration constraints during that period included ‘uncertainty about a successful survival in a new place’, ‘language barrier’, ‘lack of funds for moving’, ‘family circumstances’ and ‘fear of hostility from local residents’. Russian emigrants of that period faced unfamiliar conditions and had difficulties with adapting to the peculiarities of living in the host countries (Ushkalov and Malakha 1999: 68; Zajonchkovskaya 2003; Osipov 2014).

The second period (2000–2011)

A new period in the development of post-Soviet migration from Russia starts in the 2000s. According to the Rosstat, about 828,000 citizens left Russia from 2000 (see Table 4).

During this period the discrepancies between Russian and foreign statistics became more noticeable (see Table 6). The reasons are given above. For example, in the 1990s the discrepancy between Russian and German data was 25–30 per cent, but in the 2000s it increased to 45–78 per cent (see Table 5). According to our estimates, at least 1.5 million Russians went abroad for permanent residence in the 2000s.

Stabilization of the domestic political situation and improvement of the socio-economic situation in Russia (in 2000–2010 the country's real GDP increased by 1.75 times, the population's real expendable income increased by 2.79 times, the number of people living below the poverty line decreased from 29 to 12.6 per cent, as well as reforms of immigration legislation in a number of countries of destination preferred by Russian migrants (at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, changes in immigration policy were made, in particular, in Australia, the UK, Germany, Italy, Canada, the Netherlands, the USA, Sweden) contributed to a steady decline in the number of Russian emigrants and the transformation of the structure of emigration flows (Council of Europe 2006; Denisenko et al. 2003: 70; Osipov 2014; Rosstat 2010b: 36). The adaptation of Russian citizens to the new socioeconomic conditions also contributed to the decrease in the scale of emigration from Russia.

Table 4

Dynamics of Russian emigration in 2000–2011

|

Year |

The number of emigrants, |

% compared to the previous year |

|

2000 |

145,720 |

67.8 |

|

2001 |

121,166 |

83.1 |

|

2002 |

100,732 |

83.1 |

|

2003 |

89,971 |

89.3 |

|

2004 |

76,570 |

85.1 |

|

2005 |

66,820 |

87.3 |

|

2006 |

51,791 |

77.5 |

|

2007 |

45,071 |

87.0 |

|

2008 |

37,982 |

84.3 |

|

2009 |

30,869 |

81.3 |

|

2010 |

31,734 |

102.8 |

|

2011 |

29,467 |

92.9 |

Note: The number of citizens of the Russian Federation who left in 2002–2011.

Source: Data were collected from the Rosstat 2001–2012.

Table 5

Comparison of Russian and German statistics on the emigration

of Russian citizens to Germany in the 1990s and 2000s

|

1992 |

1997 |

2002 |

2005 |

2007 |

2009 |

|

|

Data from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany, people |

84,509 |

67,178 |

77,403 |

42,980 |

20,487 |

18,615 |

|

Rosstat data, people |

62,700 |

48,363 |

42,231 |

21,458 |

6,486 |

4,115 |

|

Discrepancy between Russian and German data |

21,809 |

18,815 |

35,172 |

21,522 |

14,001 |

14,500 |

|

The proportion of the migration flow unaccounted for by Rosstat |

25.8 % |

28.0 % |

45.4 % |

50.1 % |

68.3 % |

77.9 % |

Source: Rosstat 2000: 320; Rosstat 2012b: 113. Destatis 2021.

In the 1990s, most of the Russian emigrants went to three countries (Germany, Israel and the United States). In the 2000s, however, the geography of the emigrants' destination broadened significantly, and the distribution of emigrants among countries gradually levelled off. In 2000, 83.4 per cent of Russian citizens emigrated to Germany, Israel and the United States, while in 2010 only 49.6 per cent of emigrants settled in these countries (Rosstat 2001a; 2010a).

Table 6

Comparison of Rosstat and OECD

statistics on the emigration

of Russian citizens in the 2000s

|

Countries of Destination |

2001 |

2003 |

2005 |

2007 |

2009 |

2011 |

|

Australia, Data from the OECD, people |

599 |

704 |

901 |

673 |

1,213 |

1,090 |

|

Australia, Data from the Rosstat, people |

184 |

146 |

209 |

139 |

172 |

249 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, people |

415 |

558 |

692 |

534 |

1041 |

841 |

|

Canada, Data from the OECD, people |

4,073 |

3,718 |

3,972 |

2,983 |

2,931 |

1,963 |

|

Canada, Data from the Rosstat, people |

812 |

701 |

628 |

571 |

457 |

471 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

3,261 |

3,017 |

3,344 |

2,412 |

2,474 |

1,492 |

|

Czech Republic, Data from the OECD, people |

712 |

1,841 |

3,300 |

6,695 |

4,115 |

2,146 |

|

Czech Republic, Data from the Rosstat, people |

158 |

172 |

215 |

372 |

288 |

298 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

554 |

1,669 |

3,085 |

6,323 |

3,827 |

1,848 |

|

Finland, Data from the OECD, people |

2,539 |

1,665 |

2,081 |

2,488 |

2,336 |

2,795 |

|

Finland, Data from the Rosstat, people |

980 |

737 |

737 |

692 |

685 |

480 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

1,559 |

928 |

1,344 |

1,796 |

1,651 |

2,315 |

|

France, Data from the OECD, people |

1,401 |

2,380 |

3,027 |

2,895 |

3,408 |

3,784 |

|

France, Data from the Rosstat, people |

140 |

174 |

204 |

221 |

198 |

272 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

1,261 |

2,206 |

2,823 |

2,674 |

3,210 |

3,512 |

|

Italy, Data from the OECD, people |

2,291 |

4,256 |

2,881 |

3,004 |

4,061 |

4,269 |

|

Italy, Data from the Rosstat, people |

163 |

186 |

249 |

254 |

265 |

370 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

2,128 |

4,070 |

2,632 |

2,750 |

3,796 |

3,899 |

Table 6 (continued)

|

Countries of Destination |

2001 |

2003 |

2005 |

2007 |

2009 |

2011 |

|

Spain, Data from the OECD, people |

4,644 |

4,636 |

7,752 |

7,276 |

5,288 |

7,635 |

|

Spain, Data from the Rosstat, people |

220 |

255 |

320 |

388 |

318 |

405 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

4,424 |

4,381 |

7,432 |

6,888 |

4,970 |

7,230 |

|

USA, Data from the OECD, people |

20,313 |

13,935 |

18,055 |

9,426 |

8,238 |

7,944 |

|

USA, Data from the Rosstat, people |

4,527 |

3,199 |

4,040 |

2,108 |

1,440 |

1,422 |

|

Discrepancy between Rosstat and OECD data, % |

15,786 |

10,736 |

14,015 |

7,318 |

6,798 |

6,522 |

Source: Rosstat 2007: 124; Rosstat 2012b: 113; OECD. 2021.

Table 7

Main destination countries for Russian emigrants in 2000–2011

|

Destination country |

Number of emigrants |

Share in the total number |

|

Germany |

247,904 |

64.2 % |

|

Israel |

33,874 |

8.8 % |

|

USA |

29,000 |

7.5 % |

|

Finland |

9,305 |

2.4 % |

|

Canada |

7,554 |

2.0 % |

|

Spain |

3,694 |

1.0 % |

|

Estonia |

3,495 |

0.9 % |

|

Czech Republic |

3,170 |

0.8 % |

|

Italy |

2,995 |

0.8 % |

|

Lithuania |

2,912 |

0.8 % |

|

Latvia |

2,835 |

0.7 % |

|

China |

2,778 |

0.7 % |

|

France |

2,480 |

0.6 % |

|

UK |

2,414 |

0.6 % |

|

Australia |

2,139 |

0.6 % |

Note: Except for emigrants to the post-Soviet states.

Source: Data were collected from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat 2001–2012).

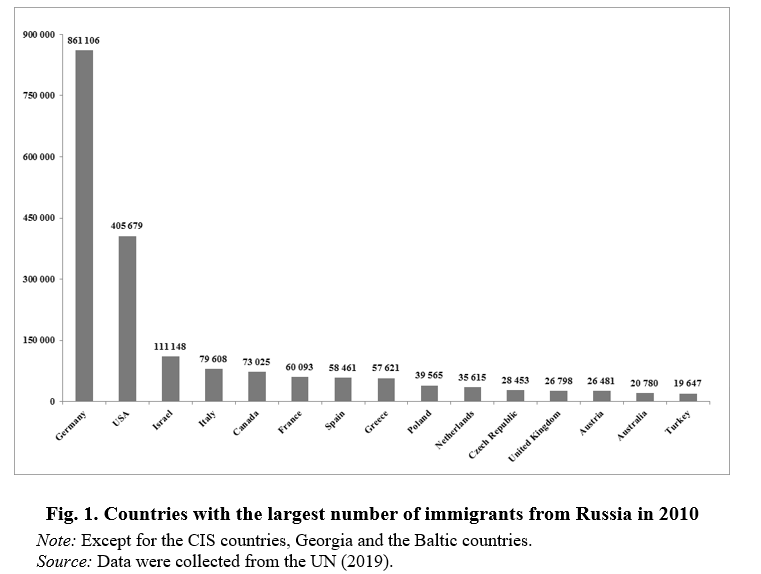

In the 2000s, the list of countries where Russians go for permanent residence expanded. According to Russian statistics, the main countries of destination for Russian emigrants during this period were: Germany, the USA, Israel, Finland, Canada, Spain, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, China, France, the UK and Australia (see Table 5). According to the UN data, in 2010 immigrants from Russia lived in 100 countries, their number exceeding 19,000 people in 15 countries (see Figure 1), and 1,000 people, in 60 countries. In 2000–2010, the most significant increase in the number of Russian immigrants was observed in Italy (by 64,792 people), in the USA (by 56,864 people), in Spain (by 50,161 people), in France (by 37,333 people), in the Czech Republic (by 21,888 people), in the Netherlands (by 20,792 people), in Canada (by 22,690 people), in the UK (by 11,673 people), in Norway (by 10,699 people), in Sweden (by 8,988 people), and in Cyprus (by 8,260 people) (UN 2019). During the same period, the naturalization process in some countries contributed to a formal decrease in the number of Russian immigrants (among others, in Germany, Greece, Israel and Finland) (Denisenko 2003; Ryazantsev 2018).

The age structure of emigrants, compared to the Russian population in general, is shifted toward younger ages, mainly due to a larger share of the working age group among the emigrants. The emigration flows have been dominated by women. Thus, in 2009 women accounted for 61 per cent of Russian immigrants to Germany, 68 per cent of immigrants to Spain, 83 per cent to Italy, 62 per cent to Norway and 59 per cent to Finland. This phenomenon is largely due to the emigration of women through marriage (Iontsev et al. 2016; Ryazantsev et al. 2018).

The main channels of emigration during that period were: 1) labour migration (the globalization of the labor market facilitates transnational movement of highly skilled migrants, while the developed countries complicate the immigration of unskilled labor); 2) intellectual migration (the ‘brain circulation’ becomes predominant, when Russian scientists work abroad for a certain period of time, mainly doing experimental work on advanced equipment); 3) forced migration (in the 2000s, several thousand Russian citizens applied for asylum abroad every year); 4) educational migration (the growth of the population's income and globalization contributed to the increase in the scale of educational emigration, there is a tendency for an increase in the number of students who did not return to Russia after completing their studies abroad); 5) marriage emigration of women (5,000–6,000 Russian women are estimated to have annually emigrated abroad with the purpose to marry, whereas the importance of economic factors of marriage emigration decreased, the main urge for Russian women to marry abroad was caused by a crisis of the Russian family model); 6) business emigration (a stratum of wealthy emigrants was formed by those who had made a fortune in the 1990s, the emigration being accompanied by the export of capital); 7) emigration of children through international adoption (in 2000–2011, almost 66,000 Russian children were adopted by foreigners); 8) family reunification (an increase in the communities of Russian immigrants in foreign countries facilitated the process of moving and settling for new emigrants) (Aleshkovski et al. 2018; Denisenko 2013; Mukomel 2005; Potapova 2017; Ryazantsev 2015, 2016; Ryazantsev and Khramova 2018; Riazantsev et al. 2018; Ryazantsev et al. 2021; Savoskul 2016; Vorobyeva and Grebenuk 2016).

Analyzing the results of sociological data of the 2000s, we can conclude that in this period the ‘focus’ of push factors shifted from the crisis reasons to the socio-economic reasons for emigration (Savoskul 2011). At the same time, a number of problems of the 1990s lost their sharpness and ceased to be of decisive importance in the formation of emigration attitudes. The content of socio-economic factors changed. Economic growth largely helped to solve the problem of unemployment, the severity of political confrontation in the country and the threat of its disintegration decreased, and the crime situation improved. However, the problems of the quality, security and stability of life came to the fore.

In the second period, emigration to non-CIS countries loses its ethnic character, and ceases to be the lot of the elite. On the whole, emigrants were relatively young, had a relatively high level of education, spoke foreign languages, knew the peculiarities of the host countries' immigration policies, which allowed them to integrate fairly easily into the host societies. In the 2000s, communities of new Russian immigrants increasingly became a significant numerical and socio-economic component in many countries. In some cases, they became intermediaries for projects with Russian partners in the field of business management, trade, education, scientific and technical cooperation. In that period, Russian citizens were increasingly involved in ‘soft emigration’, moving abroad for a certain period of time or living in two countries (having real estate and business abroad, and sometimes a residence permit or second citizenship). Also, the return migration (re-emigration) of Russian citizens was evolving (one re-emigrant in every five new emigrants) (Mukomel 2005: 59; Ryazantsev and Grebenyuk 2014; Ryazantsev 2015).

The third period (2012–2020)

The third period of post-Soviet emigration from Russia began in 2012 and ended in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Rosstat, about 530,000 Russian citizens left Russia from 2012 to 2020. According to our estimates, more than 750,000 Russians went abroad for permanent residence in the 2010s (Aleshkovski et al. 2018). However, the aggravation of the internal political and socioeconomic situation in Russia resulted in a steady increase in the number of Russian emigrants from 2015 to 2020 (see Table 7).

Table 8

Dynamics of Russian emigration in 2012–2020

|

Year |

The number of emigrants, |

% compared to the previous year |

|

2012 |

46,687 |

158,4 |

|

2013 |

47,439 |

101,6 |

|

2014 |

52,235 |

110,1 |

|

2015 |

51,846 |

99,3 |

|

2016 |

58,739 |

113,3 |

|

2017 |

66,735 |

113,6 |

|

2018 |

73,344 |

109,9 |

|

2019 |

73,382 |

100,1 |

|

2020 |

57,476 |

78,3 |

Note: The number of citizens of the Russian Federation who left the Russian Federation.

Source: Data were collected from the Russian Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat, 2013–2021).

One should note that from 2011, the methodology for registering migrants changed in Russia. Migrants who were registered in the place of residence for a period of nine months or more (previously, more than one year) began to be counted as permanent residents. In addition, since 2012, international migrants who exceeded the authorized period of stay in Russia were automatically removed from the register and included in the number of those who left the country. The new methodology for registering migration since 2012 has radically changed the recorded characteristics of the emigration flows from Russia, including the distribution of emigrants by destination countries. The largest number of those who left Russia began to be recorded in labor-exporting countries (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, China, North Korea, etc.). In this regard, in order to assess the real scale of Russian emigration, it becomes necessary to single out only Russian citizens in the total number of those who left (Ryazantsev 2018; Ryazantsev et al. 2021; Chudinovskikh and Stepanova 2020).

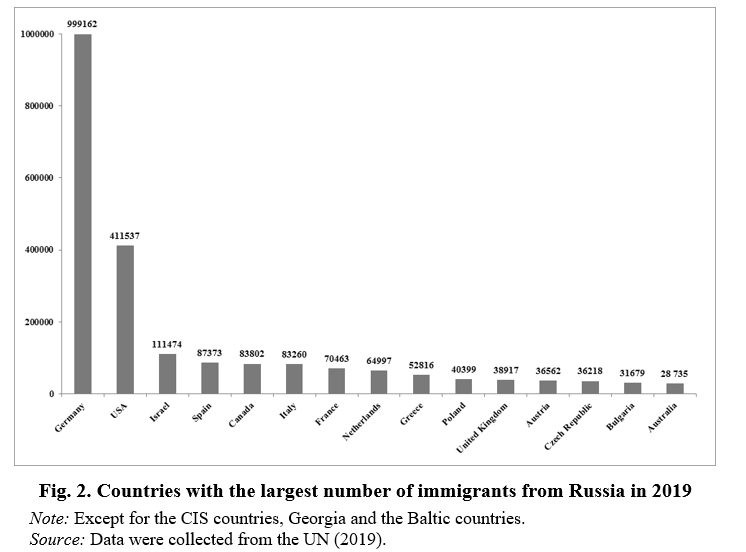

According to the UN, migrants from Russia lived in over 100 countries in 2019, their number exceeding 28,000 people in fifteen countries, and 1,000 people, in 64 countries (see Fig. 2). In 2010–2019, the most significant increase in the number of Russian immigrants was in Germany (138,056 people), the Netherlands (29,382), Spain (28,912), Bulgaria (13,739), the UK (12,119), Canada (10,777), France (10,370) and Austria (10,081). A decrease in the number of Russian immigrants in Greece and Cyprus, as well as their slight increase in Israel is explained by the naturalization process (UN 2019).

According to both Russian and foreign statistics, the third stage of emigration flows from Russia retained high indicators of the quality of human capital, that is high educational levels, and a relatively young age of emigrants. In 2019, the share of people with higher and incomplete higher education among Russian emigrants to Australia was44 per cent, the United Kingdon – 42 per cent, Germany – 36 per cent, Israel – 37 per cent, Canada – 52 per cent, and the USA – 39 per cent (Rosstat 2020). According to the 2015 microcensus, about 25 per cent of Russians had higher or incomplete higher education, so the immigration policy of developed countries has also been aimed at stimulating the influx of young educated people from Russia. The average age of Russian emigrants remains significantly younger than the average age of the country's population as a whole, mainly due to the larger share of the working age group. Thus, in 2019 about 80 per cent of Russian citizens who left the country were of working age.

One can hardly ignore another practical aspect that became a significant factor in emigration in the 2010s. The steady depreciation of the Russian currency in 2014–2020 led to a significant increase in wages abroad in ruble terms, thus making employment abroad even more lucrative.

In the above-mentioned period, the main channels for emigration were: 1) labour migration; 2) educational migration; 3) forced migration; 4) marriage emigration of women; 5) business emigration (the programs ‘citizenship in exchange for investments’ are spreading, investment migration becoming an important channel for the legalization of Russian migrants); 6) family reunification (there has been a growing contribution of the ‘other relatives’ group, which includes brothers, sisters, nephews, grandmothers, grandfathers and distant relatives) (Aleshkovski et al. 2020; Baykov et al. 2018; Denisenko 2020; Iontsev et al. 2016; Potapova 2017; Ryazantsev and Khramova 2018; Riazantsev et al. 2018; Riazantsev et al. 2021; Savoskul 2016; Vorobyeva and Grebenuk 2016). The channel of child emigration through international adoption practically ceased to operate by 2019. Thus, just 289 Russian children were adopted by foreigners in 2019.

The analysis of the results of sociological research in the 2010s allows concluding that the emigration was characterized by a continuing shift of the push factor towards economic determinants (WCIOM 2012, 2018; Levada 2015, 2019; Herbst and Erofeev 2019). At the above-mentioned stage, the increasing scale of emigration from Russia was accompanied by involving new social groups, including entrepreneurs and members of their families, former government officials, their families, relatives of the members of the political and financial elite. Family reunification became one of the main channels for the entry and naturalization of immigrants from Russia. Communities of Russian immigrants in the main host countries were magnets for close and distant relatives and acquaintances of emigrants. The new generation of Russian emigrants, having the freedom of movement, were, more or less, people of the global world (‘global Russians’). They had a good idea of the peculiarities of life and work in a particular country, speak foreign languages, and adapted more easily to the host society (Riazantsev et al. 2021).

Discussion

Even though in this work we have analyzed the data from both Russian and foreign statistics, it is hardly possible to precisely estimate the scale of Russian emigration in the period from 1990 to 2020. Our estimates of the number of Russian emigrants, based on the data from the statistical services of the main destination countries for Russian emigrants and the figure provided by the Rosstat, range from 4.3 to 6.3 million people. It should be noted that the geography of Russian emigration has expanded considerably in recent years. In the course of the study, we found statistical information on immigration in a number of new destination countries for Russian emigrants to be incomplete, which considerably reduces the accuracy of our estimate.

Another important issue requiring a more detailed study is the assessment of the loss of national human capital because of emigration. The high level of education in Russia makes a wide range of professions wanted abroad. However, the opportunity to obtain higher education at the expense of the state followed by the freedom to move abroad and find a job there, results in direct financial losses for the state. These losses amount to billions of US dollars. This problem is not unique to Russia, and many countries face it. It needs to be discussed, and a solution for it should be searched for at the multinational level.

As part of further research on Russian emigration, it is necessary to answer the question which becomes more and more relevant at the current stage of emigration from Russia: ‘Does any resettlement abroad mean emigration?’ Within the framework of the current stage of development of Russian emigration, we have identified a trend towards an increase in the resettlement of Russians to countries that, in terms of the socio-economic development, significantly lag behind the leading countries in terms of receiving Russians. In the 2010s, the emigration of Russians to Estonia, the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Poland increased considerably. For example, 1,692 Russians migrated to Estonia in 2019, which is 4.7 times more than in 2010. This trend may be indicative of Russians being granted a second citizenship or a residence permit abroad for traveling unhindered between European countries and doing business there. As a result, it is not emigration that is taken account of in this case, but a legalizing procedure, or the format of a Russian's life in two countries.

The study has established a decrease in the severity of ‘push’ factors in 1990–2010. The analysis of the results of sociological research conducted during the 2010s (WCIOM 2012, 2013, 2018; Levada 2015, 2019) allows concluding that at the present stage the main push factors are: unfavorable economic situation, volatility of the national currency exchange rate, risks of external and internal ‘shocks’ to the national economy, lack of confidence in the future, reduced employment opportunities and career growth, lower wages, insufficient social protection of the population, unfavorable business conditions, low social mobility, feeling that the country is not progressing or even deteriorating, limited opportunities for career advancement, low quality of healthcare, deteriorating quality of education, political situation, threat of persecution for account of one's own social and political stance, distrust of law enforcement agencies.

The main ‘pull’ factors in foreign countries are: higher wages, opportunities for real improvement in living standards, more comfortable living conditions, great opportunities for self-realization and career, a developed social infrastructure, guarantees of good social security, stable and safe life, a more comfortable climate, high quality medical services, better opportunities for receiving quality education, favorable business and investment climate, an opportunity to gain new experiences, guarantees of citizens' rights and freedoms, political freedoms, and the desire to secure a good future for children.

Another issue that requires a separate study is the influence of natural, climatic and environmental factors on the emigration of wealthy strata of Russians. The geographical location of most of Russia in rather harsh climatic zones can be a considerable ‘push’ factor that manifests itself in internal Russian migration. In many ways, the high rates of emigration to Spain, Italy, Turkey, and Cyprus can be explained, among other things, by the favorable climate, temperature regime and environmental conditions.

An important debating point is the forecasting of emigration from Russia in the period up to 2030. Proceeding from the data obtained, the extrapolation method does not fully meet the requirements of such a study. The transformation of ‘push factors’, the closure of borders during the COVID-19 pandemic, the unstable global economy, the possible weakening of ‘pull factors’ and the departure of the majority of the most mobile social groups from Russia require the development of multifactorial scenario-based predictive models. This line of research is of practical importance primarily for Russia, as well as for potential host countries for Russian migrants.

It is a peculiarity of our research that, along with the specific scientific results obtained, we have managed to identify the directions for further emigration studies. We believe that the results of this work can be of both theoretical and practical importance. In theoretical terms, they can be used to further expand the understanding of the characteristic features of migration processes associated not only with Russia, but also with host countries for Russian emigrants. The practical focus of the study implies using its results to improve the migration policy of Russia and other countries involved in the processes of international migration, as well as the Russian policy towards compatriots living abroad.

Conclusion

Our study of the emigration flows from Russia in the period from 1990 to 2020 allows making the following conclusions concerning the evolution of the Russian emigration.

For Russia, emigration is a negative social process, primarily associated with demographic, socioeconomic and intellectual losses (Akhiezer 1999: 172). However, the concept of the state migration policy of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2025 does not duly address emigration issues (‘The emigration outflow from the country continues ... The tasks of the state migration policy of the Russian Federation ... the creation of conditions and incentives for resettlement to the Russian Federation for permanent residence of compatriots residing abroad, emigrants and certain categories of foreign citizens’), which complicates the implementation of an effective migration policy (The concept of the state migration policy… 2018). In the action plan for the implementation of the Demographic Policy Concept of the Russian Federation in 2021–2025 there are no measures in the field of emigration (Action plan for the implementation… 2021).

Russian emigration from 1990 to 2020 was accompanied not only by quantitative but also qualitative losses. The common features of the entire post-Soviet period emigration are the high level of education and qualifications of emigrants, as well as their relatively young age composition. The countries that hosted Russians, apart from solving their demographic problems, received a powerful impetus in the development of various sectors of the economy, including science and education. For example, in the 1990s Russian emigrants contributed to the development of nuclear physics and medical science in Israel, computer science, laser physics and mathematics in the United States, and bioengineering and chemistry in France. At the same time, the losses of the intellectual capital of the 1990s in Russia were not fully made up by 2020.

The present study found that there was a significant transformation of the emigration flow from Russia from 1990 to 2020. The Russian emigration became more diverse in terms of emigration channels, geographic coverage of regions of departure and countries of destination, and socio-demographic characteristics of emigrants. We have singled out three periods of emigration (1990–1999, 2000–2011 and 2012–2020), differing in the determinants of emigration, the population's emigration potential, socio-demo-graphic characteristics of migrants, channels and directions of emigration.

Over the three decades of Russian emigration from 1990 to 2020, the ‘push’ factor played a major role in the formation of million-strong flows of Russian emigrants. Over the years, it undergone a dramatic transformation. At the first stage (1990–1999) the range of reasons for leaving the country was very wide, from a threat to life to unfavorable socioeconomic conditions. At the third stage (from 2012 to 2020) the list of reasons narrowed considerably. Among these reasons, socio-economic factors became to the fore, many of them were characteristic of emigration from various countries.

In the 1990s, the most popular destinations for Russian emigration were Germany, Israel, and the United States, which accumulated over 90 per cent of the emigration flow. At the present stage, the geographical directions of emigration have remarkably diversified. Nowadays, immigrants from Russia live in 100 countries of the world, including Australia, Canada, the United States, practically in all European countries, most of the Latin American and Asian countries, and a number of countries in Africa and Oceania. Emigrants from Russia make up one of the largest socio-demographic groups of migrants in the world.

The main channels of emigration in post-Soviet Russia were: ethnic emigration, intellectual migration, forced migration, educational migration, labour migration, emigration of women for marriage, emigration for business and investment, emigration of children through international adoption and family reunification. The existence and extent of each of these channels were determined by specific historical events or processes. In the 1990s, ethnic and intellectual emigration was of particular importance. In the 2000s, this was forced migration, migration for education, emigration for work, business emigration, international adoption of Russian children, family reunification. In the 2010s, emigration for education, migration for work, emigration of women for marriage, emigration for business and investment, and family reunification were of great importance. At the present stage, the scale of the so-called ‘soft’ emigration is increasing, whereby Russian citizens effectively divide their time between two homes, owning real estate and / or businesses, having a residence permit or a second citizenship abroad. At the same time, they formally remain permanent residents of Russia, without being included in the statistics of emigrated citizens.

In 2010s, the character of emigration from Russia changed. It acquired a more ‘economic’ leaning, mainly due to the differing level and quality of life in Russia and in the main host countries. A striking example confirming this idea was the emigration of Russian IT specialists, whose departure is influenced by the difference in wages at home and abroad. It should also be noted that the socioeconomic situation in Russia in 2010s encourages the emigration of entrepreneurs and the transfer of their savings abroad.

We can conclude that in 2020 by beginning COVID-19 pandemic present-day Russian emigration became more diverse, and its development trends are largely in line with global trends. It determined the need for a diversified state policy in the field of emigration in Russia. Special attention should be paid to the study of the socio-demographic structure of Russian emigrants in the host countries, the channels of their emigration and their motives for emigration.

REFERENCES

Action plan for the implementation in 2021–2025 of the Demographic Policy Concept of the Russian Federation until 2025. Approved by Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of September 16, 2021 No. 2580-r. URL: http://government.ru/news/43296/ (accessed on: 30.05.2023). Original in Russian (План мероприятий по реализации в 2021–2025 годах Концепции демографической политики Российской Федерации на период до 2025 года. Утвержден Распоряжением Правительства Российской Федерации от 16 сентября 2021 г. № 2580-р).

Akhiezer, A. S. 1999. Emigration as a Status Indicator of the Modern Russian Society. Mir Rossii 4: 163–175. Original in Russian (Ахиезер А. С. Эмиграция как индикатор состояния российского общества. Мир России 4: 163–175.).

Aleshkovski, I. A. 2011. International Migration Trends in Contemporary Russia in the Context of Globalization. Vek globalizacii 1: 159–181. Original in Russian (Алешковский И. А. Тенденции международной миграции населения в современной России в условиях глобализации. Век глобализации 1: 159–181).

Aleshkovski, I., Grebenuk, A., Likhacheva, P. 2020. ‘Foreign Land, I Greet You!’: the Evolution of Russian Emigration in the Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries. ISTORIYA 11. № 12 (98). DOI: 10.18254/S207987840012964-9. Original in Russian (Алешковский И., Гребенюк А., Лихачева П. «Страна чужая, здравствуй»: эволюция российской эмиграции в конце XX — начале XXI вв. История 11, 12 (98)).

Aleshkovski, I., Grebenyuk, A., and Vorobyeva, O. 2018. The Evolution of Russian Emigration in the Post-Soviet Period. Social Evolution & History 17 (2): 140–155. DOI: 10. 1002/eet.1601.

Aron, L. 1991. The Russians are Coming ... And the West Needs an Immigration Policy that Makes Sense. The Washington Post, 27 January. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/ archive/opinions/1991/01/27/the-russians-are-coming-and-the-west-needs-an-immigrati-on-policy-that-makes-sense/ada77273-2440-4c12-98c7-a5e4933c076c/. Accessed Janu-ary 10, 2022.

Baykov, A. A., Lukyanets, A. S., Pismennaya, E. E., Rostovskaya, T. K., Ryazantsev, S. V. 2018. Youth emigration from Russia: Scale, Channels, Consequences. Sociologicheskie issledovaniya 11: 75–84. DOI: 10.31857/SO13216250002787-8. Original in Russian (Байков А. А., Лукьянец А. С., Письменная Е. Е., Ростовская Т. К., Рязанцев С. В. Эмиграция молодежи из России: масштабы, каналы, последствия. Социологические исследования 11: 75–84.).

Brym, R. J. 1992. The Emigration Potential of Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Russia: Recent Survey Results. International Sociology 7 (4): 387–395. DOI: 10. 1177/026858092007004001.

Chudinovskikh, O., Stepanova, A. 2020. On the quality of the federal statistical observation of migration processes. Demographic review 7 (1): 54–82. DOI: 10.17323/demre-view.v7i1.10820. Original in Russian (Чудиновских О., Степанова А. О качестве федерального статистического наблюдения за миграционными процессами. Демографическое обозрение 7(1): 54–82).

Council of Europe. 2006. Towards a Migration Management Strategy Challenges for Countries of

Origin. URL: https://www.coe.int/t/dg3/migration/archives/Documentation/Migration%20management/

CDMG_2006_11e%20Final%20Report%20_MG-R-PE_en.pdf.

Accessed December 31, 2021.

Denisenko, M. 2003. Emigration from Russia According to Foreign Statistics. Mir Rossii 12 (3): 157–169. Original in Russian (Денисенко М. Эмиграция из России по данным зарубежной статистики. Мир России 12 (3): 157–169).

Denisenko, M. 2013. Historical and Current Trends in Emigration from Russia. International Migration Processes: Trends, Challenges and Outlook. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/historical-and-current-trends-in-emigr.... Accessed December 31, 2021.

Denisenko, M. 2020. Emigration from the CIS Countries: Old Intentions – New Regularities. In Denisenko M., Strozza S., Light M. (eds), Migration from the Newly Independent States. Societies and Political Orders in Transition. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36075-7_5.

Denisenko, M. B., Kharaeva, O. A., Chudinovsky, O. S. 2003. Immigration Policy in the Russian Federation and Western Countries. Moscow: IEP. Original in Russian (Денисенко М. Б., Хараева О. А., Чудиновский О. С. Иммиграционная политика в российской федерации и странах Запада. Москва: ИЭП).

Destatis. 2021. Genesis-Online Database. URL: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online. Accessed December 31, 2021.

EMISS. 2021. The Unified Interdepartmental Statistical Information System. URL: https:// www.fedstat.ru/indicator/43513. Accessed December 31, 2022.

Herbst, J., Erofeev, S. 2019. The Putin Exodus: The New Russian Brain Drain. Washington: Atlantic Council.

IOM. 2019. Glossary on Migration. URL: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Iontsev, V. A., Lebedeva, N. M., Nazarov, M. V., Okorokov, A. V. 2001. Emigration and Repatriation in Russia. Moscow. Original in Russian (Ионцев В. А., Лебедева Н. М., Назаров М. В., Окороков А. В. Эмиграция и репатриация в России. Москва).

Iontsev, V. A., Ryazantsev, S. V., Iontseva, S. V. 2016. Emigration from Russia: New Trends and Forms. Economy of Region 12 (2): 499–509. DOI: 10.15826/recon.2016.2.2.019.

Law of the USSR. 1991. The Law of the USSR of May 20, 1991 № 2177-1 “About the Order of Exit from the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics and Entry into the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics of citizens of the USSR”. URL: http://www.consultant.ru/do-cument/cons_doc_LAW_1408/fe58e4c484d58073a751af7920ec463f64e9309b/. (date of access: 31.12.2021). Original in Russian (Закон СССР от 20.05.1991 г. №2177-1 «О порядке выезда из Союза Советских Социалистических Республик и въезд в Союз Советских Социалистических Республик граждан СССР»).

Lee, E. S. 1966. A Theory of Migration. Demography 3: 47–57. DOI: 10.2307/2060063.

Levada. 2015. Russian Feelings on Emigration. Yuri Levada Analytical Center Survey. March 25. URL: https://www.levada.ru/en/2015/03/25/russian-feelings-on-emigration/. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Levada. 2019. Emigration Attitudes. Yuri Levada Analytical Center Survey, February 20. URL: https://www.levada.ru/en/2019/02/20/emigration-attitudes/. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Lokosov, V. V., Rybakovskiy, L. L. 2014. (eds). Migration Processes in Russia. Moscow: Ekon-Iform. Original in Russian (Локосов В. В., Рыбаковский Л. Л. (ред.), Миграционные процессы в России. Москва: Экон-Информ).

Mukomel, V. I. 2005. Migration Policy in Russia: Post Soviet Contexts. Moscow: Dipol'-T. Original in Russian (Мукомел В. Миграционная политика России: Постсоветские контексты. Москва: Диполь-Т).

OECD. 2021. International Migration Database. URL: https://stats.oecd.org. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Osipov, G. V. 2014. Reforming Russia: Myths and Reality. Moscow: ISPI RAN. Original in Russian (Осипов Г. В. Реформирование России: мифы и реальность. М.: ИСПИ РАН).

Polyan, P. 2005. Emigration: Who and When Left Russia in 20th Century. In Glezer O., Polyana P. (eds.), Russia and Its Regions in the 20th Century: Territory – Settlement – Migration (pp. 493–519). OGI, Moscow. Original in Russian (Полян П. Эмиграция: кто и когда в XX веке покидал Россию. Россия и её регионы в XX веке: территория – расселение – миграции / Под ред. О. Глезер и П. Поляна. М.: ОГИ).

Potapova, A. A. 2017. Emigration from Russia: Current Decade. Demoscope Weekly 7019-720. URL: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2017/0719/tema01.php. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Riazantsev, S., Pismennaya, E., Lukyanets, A., Sivoplyasova, S., Khramova, M. 2018. Modern Emigration from Russia and Formation of Russian-Speaking Communities Abroad. Mirovaya ekonomika i mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya 62 (6): 1–15. DOI: 0.20542/0131-2227-2018-62-6-93-107. Original in Russian (Рязанцев С., Письменная Е., Лукьянец А., Сивоплясова С., Храмова М. Современная эмиграция из России и формирование русскоговорящих сообществ за рубежом. Мировая экономика и международные отношения 62 (6): 1–15).

Rosstat. 1996. Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Российский статистический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2000. Demographic Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Демографический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2001a. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2000. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2000 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2001b. Demographic Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Демографический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2001c. Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Российский статистический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2002. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2001. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2001 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2003. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2002. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2002 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2004. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2003. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2003 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2005. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2004. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2004 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2006. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2005. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2005 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2007a. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2006. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2006 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2007b. Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Российский статистический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2008. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2007. Statistical bulletin. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2007 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2009. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2008. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/B09_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2008 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2010a. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2009. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/free/b10_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2009 году. Статистический бюллетень Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2010b. Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Российский статистический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2011. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2010. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b11_107/Main.htm. (Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2010 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2012a. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2011. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b12_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2011 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2012b. Russian Statistical Yearbook. Moscow: Rosstat. Original in Russian (Российский статистический ежегодник. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2013. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2012. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b13_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2012 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2014. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2013. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b14_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2014 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2015. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2014. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b15_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2014 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2016. The Size and Migration of population of the Russian Federation in 2015. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b16_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2015 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2017. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2016. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b17_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2016 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2018. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2017. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b18_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2017 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2019. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2018. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b19_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2018 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2020. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2011. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://gks.ru/bgd/regl/b20_107/Main.htm. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2019 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2021a. The Size and Migration of Population of the Russian Federation in 2020. Statistical bulletin. URL: https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/q9wFke4y/bul-migr20.xlsx. Original in Russian (Численность и миграция населения Российской Федерации в 2020 году. Статистический бюллетень. Москва: Росстат).

Rosstat. 2021b. Migration. URL: https://gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/population/demo/migr1_bd.htm. Accessed December 31, 2021.

Ryabtsev, A. 2011. Why do our Fellow Citizens Emigrate from the Country. Komsomolskaya pravda. October 14. URL: https://www.kp.ru/daily/25770/2754926/. Original in Russian (Рябцев А. Почему наши сограждане эмигрируют из страны. Комсомольская правда, 14 октября). Accessed December 31, 2021.

Ryazantsev, S. V. 2016. Emigrants from Russia: Russian Diaspora or Russian-speaking community? Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya 12: 93–104. Original in Russian (Рязанцев С. В. Эмигранты из России: русская диаспора или русскоговорящие сообщества? Социологические исследования 12: 93–104).

Ryazantsev, S. V., Grebenyuk, A. A. 2014. ‘Our’ abroad. Russians, Russian-Speakers, Compatriots: Resettlement, Integration and Return Migration to Russia. Moscow: ISPI RAN. Original in Russian (Рязанцев С. В., Гребенюк А. А. «Наши» за границей. Русские, россияне, русскоговорящие, соотечественники: расселение, интеграция и возвратная миграция в Россию. М.: ИСПИ РАН).

Ryazantsev, S. V., Khramova, M. N. 2018. Factors of Emigration from Russia: Regional Features. Ekonomika regiona 14 (4): 1298–1311. Original in Russian (Рязанцев С. В., Храмова М. Н. Факторы эмиграции из России в постсоветский период: региональные особенности. Экономика региона 14 (4): 1298–1311).

Ryazantsev, S. V., Pismennaya, E. E., Ochirova, G. N. 2021. Russian-Speaking Population in Far-Abroad Countries. Vestnik MGIMO-Universiteta 14 (5): 81–100. DOI: 10.24833/2071-8160-2021-5-80-81-100. Original in Russian (Рязанцев С. В., Письменная Е. Ф. Очирова Г. Н. Русскоязычное население в странах дальнего зарубежья. Вестник МГИМО-Университета 14 (5): 81–100).

Savoskul, M. S. 2016. Emigration from Russia to the non-CIS Countries during the Late 20th – early 21st century. Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta 2: 44–54. (Series 5. Geography). Original in Russian (Савоскул М. С. Эмиграция из России в страны дальнего зарубежья в конце XX– начале XXI века. Вестник Московского университета. Серия География. 2: 44–54).

Schultz, T. W. 1981. Investing in People: The Economics of Population Quality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

The Concept of the State Migration Policy of the Russian Federation for the Period up to 2025. 2018. URL: https://legalacts.ru/doc/kontseptsija-gosudarstvennoi-migratsionnoi-politiki-rossiiskoi-federatsii-n.... Original in Russian (Концепция государственной миграционной политики Российской Федерации на период до 2025 года). Accessed December 31, 2021.

UN – United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. 2019. International Migrant Stock 2019. United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/ Stock/Rev.2019.

Ushkalov, I. G., Malakha, I. A. 1999. Brain Drain: Scope, Causes, Consequences. Moscow: Editorial URSS. Original in Russian (Ушкалов И. Г., Малаха И. А. Утечка умов: масштабы, причины, последствия. М.: Эдиториал УРСС).

Vishnevsky, A., Zayonchkovskaya, J. 1991. Migration from the USSR: the Fourth Wave. Working papers of the Center for Demography and Human Ecology. Issue 3. Moscow. Original in Russian (Вишневский А., Зайончковская Ж. Миграция из СССР: четвертая волна. М.).

Vorobyeva, O. D., Grebenuk, A. A. 2016. Emigration from Russia in the end of XX – beginning of XXI centuries. Analytical report. Moscow: Komitet grazhdanskikh initsiativ. Original in Russian (Эмиграция из России в конце XX – начале XXI века).

WCIOM. 2013. Emigration Attitudes in Russia. WCIOM Analytical Center Survey. July 16. URL: https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/emigraczionnye-nastroe-niya-rossiyan. Original in Russian (ВЦИОМ. Эмиграционные настроения россиян). Accessed December 31, 2021.

WCIOM. 2018. Emigration Attitudes in Russia. WCIOM Analytical Center Survey. July 2. URL: https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/emigraczionnye-nastroe-niya-rossiyan-2018. Original in Russian (ВЦИОМ. Эмиграционные настроения россиян). Accessed December 31, 2021.

WCIOM. 2012. Why are They Leaving Russia? The Opinion of Potential Emigrants. WCIOM Analytical Center Survey. March 28. URL: https://wciom.ru/analytical-re-views/analiticheskii-obzor/pochemu-uezzhayut-iz-rossii-mnenie-potencz.... Original in Russian (ВЦИОМ. Почему уезжают из России? Мнение потенциальных эмигрантов). Accessed December 31, 2021.

Zajonchkovskaya, Zh. A. 2003. Emigration to Far-Abroad Countries. Mir Rossii 12: 145–150. Original in Russian (Зайончковская Ж. Эмиграция из России в дальнее зарубежье. Мир России 12: 145–150).